College of Law Remembers Assassination of JFK 60 Years Later

November 13, 2023

As the 60th anniversary of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination approaches, a group of esteemed Dallas journalists gathered at the UNT Dallas College of Law to share their memories, insights and experiences. A pioneering business leader and former Texas state legislator joined them in a provocative and enlightening discussion.

“JFK inspired a generation of young people,” said Tom Huang, Assistant Managing Editor for Journalism Initiatives at The Dallas Morning News, which cohosted the event. “His death shattered dreams and had a lasting impact.”

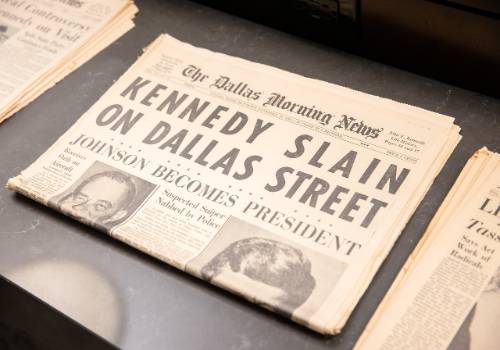

Participants and attendees recalled the newspaper’s special edition, published 20 years after the killing, which included a sobering, reflective message from the editor. “The enormity of the crime etched an enduring sorrow on the national consciousness. Consumed by uncertainly, with the world looking on, the city of Dallas examined itself and was examined; judged itself and was judged,” wrote Burl Osborne, who later became publisher.

At the time JFK was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963, Dallas was about a tenth the size it is today, with a population of 670,000. It had a reputation described by panelists in several ways. “Dallas was seen as right-wing and a city of haters,” recalled Helen Giddings, entrepreneur, community advocate and former Texas state representative. It was a place of “wide-brimmed hats and narrow viewpoints,” said Carolyn Barta, former Dallas Morning News reporter. “It was a gunslinger city and a patriarchal society that excluded a lot of people.”

Their comments set the scene for an even deeper conversation about Dallas then and now, the profound effects of President Kennedy’s death, and his connection to the civil rights movement.

“JFK was killed because of his position on civil rights, Giddings said emphatically. “In the homes of Black families, you would see three photos: Jesus, MLK, and JFK.” In the 1960 presidential election, almost 70 percent of African Americans voted for Kennedy, according to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Museum.

Giddings said JFK’s position evolved over time, and he became enlightened. “JFK spoke to the nation… that civil rights count,” Giddings said. After his killing, Giddings remembered, “It was a frightening time for Blacks. “They were worried the hands would turn back (on civil rights).”

Dallas Morning News reporter Michael Granberry shared his vivid childhood memory of the day JFK was assassinated. It was a week before his twelfth birthday. His mother had promised they would go see the president’s motorcade, but his father refused to let them go because of a controversial advertisement about JFK he saw in the morning paper, placed by a right-wing group.

The death of President Kennedy was “very personal” for Granbury, as he recalled with pain and sadness in his voice. The events of the day felt like “a loss of innocence, the death of innocence.” He told another story, about a visit to his girlfriend’s uncle in New York City in 1988, 26 years after the assassination. Knowing Granbury was from Dallas, the uncle told him, “I will never forgive you for killing the president.” Granbury said the man cheered against the Dallas Cowboys for the same reason--- he hated the city and everyone in it. Granberry wrote a book, Oswald Lived Here: Lives Changed by a Flash of History.

Barta said, “When the Cowboys played on TV, they (announcers) just called them the ‘Cowboys,’ not the ‘Dallas Cowboys’.” The city said, “How do we change the narrative,” Barta recollected. She said it prompted a lot of soul-searching by city leaders.

Just as the Cowboys represented what some believed was a dark cloud over Dallas, they also came to symbolize harmony. “The Cowboys helped unite (us),” said Granbury. “The Cotton Bowl, where black and white, rich and poor, sat side-by-side” watching Cowboys games, sent a message to the nation.

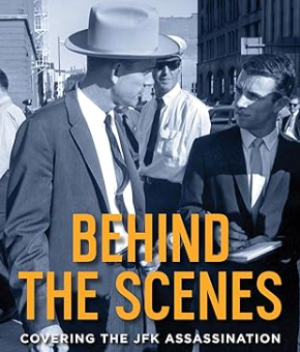

Former Dallas Times Herald reporter Darwin Payne said Dallas was viewed poorly by outsiders for years after the assassination, including internationally. Tourists to the city or Dallasites visiting other states and countries would often ask or be asked, “Who shot JFK?” he said. But by 1983, the question became, “Who shot JR?”, referring to the hit TV show Dallas, in which someone tries to kill wealthy oilman, J.R. Ewing. Payne is the author of the book, Behind the Scenes Covering the JFK Assassination, which recounts many other memories and experiences of his decades as a journalist.

Payne said the assassination prompted Dallas mayor, J. Erik Johnson, elected in 1964, to create new goals, which led to public school kindergarten and other important programs. “The city had an 81 percent white population,” Payne said. “Now white is the minority.”

That change in demographics was a transformation that took decades. Not just in population, but in power. “There were no Blacks in any political structure,” said Barta. Following the assassination and the city’s self-assessment, the first Black citizens were elected to the Dallas City Council, Board of Education, and Texas State Legislature. “Now, Dallas is such a different place. There’s no comparison,” Barta told the audience.

The UNT Dallas College of Law built an interactive exhibit, which traces the weekend of Nov. 22, 1963, step-by-step for visitors. The college is located in the former Dallas City Hall, which housed Police Headquarters, where Lee Harvey Oswald was taken after his arrest, interrogated by investigators, and shot and killed by Jack Ruby. A unique partnership led to the building's meticulous renovation, while preserving significant elements related to the assassination, including Oswald's jail cell. It is not open to the public; private tours can be arranged for small groups.

As John F. Kennedy said in 1956 while a U.S. Senator from Massachusetts, "The courage of life is often a less dramatic spectacle than the courage of a final moment; but it is no less a magnificent mixture of triumph and tragedy."